Aspirational Labor & The Mythologies of Creative Work

Everyone has to practice. If you do well at that unpaid internship, you might even get offered a job!

Before I can really commit to this YouTube thing, I've got to do something about my lips.

The thought is gone before I have time to think about it critically. I'm sitting at my desk editing a video, and at the moment all I can focus on is the funny little shape my mouth makes when I'm stumbling over my words. Before I know it, I’m Googling skin-softening Adobe Premiere plugins and wondering if there’s any B-Roll I can edit over this part of the video.

If I had more time, I might notice that in this frozen reflection I look something like my grandma Bibby.

But I don't have time. I'm working.

It should be noted that no one is paying me for this work. I'm not clocked in for an employer, unless you count Google. Or me.

The best way to describe the many hours I spend scripting, strategizing, filming, editing, and producing this piece of video content is as a form of aspirational labor. The only hope I have of profit from my hours of creative work comes from one of two future possibilities:

1. That someone might click on something in the video description and buy it from me directly.

2. That eventually, after sufficiently delighting YouTube's algorithm, I might begin to receive a cut of the money they make running ads on videos of my face and body and ideas.

In other words, I am working now in the hopes of getting paid to work later. The fact that I am spending a not-small part of these working hours criticizing and troubleshooting my own appearance is a feature, not a bug. My self-doubt and overwhelming sense of personal responsibility is a part of the design.

Aspirational Labor: Why Artists Work For Free

Aspirational labor, as defined by Brooke Erin Duffy, is “(mostly) uncompensated, independent, and propelled by the much venerated ideal of getting paid to do what you love."1 Much like an angel number or an excuse to stay in bed, once you have a name for aspirational labor you begin to see it everywhere. Unpaid internships, yoga teacher trainings, TikTok shop ad challenges, publishing ~consistently~ on Substack—all examples of the work a modern creative person might do in order to hopefully make some money later on.

For an artist swimming in the waters of "creative industry," it would seem that it pays to become a well-branded, marketable name. In order to do that, popular wisdom suggests that one should, at least for a little while, expect to work for free.

No one goes viral overnight, after all, and even those that do struggle to maintain the momentum. The grind, the hustle, the embarrassment of trying in public with no guarantee of any form of attention or reward in exchange—this is all considered to be an intrinsic part of the process, like doing bad standup for a few years before you figure out how to make people laugh.

Everyone has to practice, the story goes. True artists do it for the love of the game. If you do well at this unpaid internship, you might get offered a job. Did you know that for years Emily Weiss woke up at 5 am to write blog posts for Into The Gloss? Or that Alix Earle made dozens of videos every week before any of them actually took off?

To the aspiring self-made creative, stories like these form a glamorous, aspirational, entrepreneurial mythology. The fact that most of these Cinderellas are beautiful and young and white and blonde and likely set up to inherit a castle either way is unsurprising and therefore conveniently fades into the set dressing of the story itself.

When we’re rushing to be the next big thing (even if that big thing is just, like, being niche industry famous and/or someone who sells a respectable number of books), we forget to think about the variables. We forget to think about the value we’re creating for Fortune 500 companies every time we post. We forget about that year when we all agreed “not to dream of labor.” We’re too busy responding to the never-ending urgency of needing to be seen or, as we call it in the business, meeting the demands of the market.

I Do, In Fact, Blame Reagan

When did we decide we should all be entrepreneurs? It depends who you ask. Artisans and craftspeople and independent service providers have existed for centuries, and there is nothing particularly novel or new about humans getting paid by other humans to do a specific thing well.

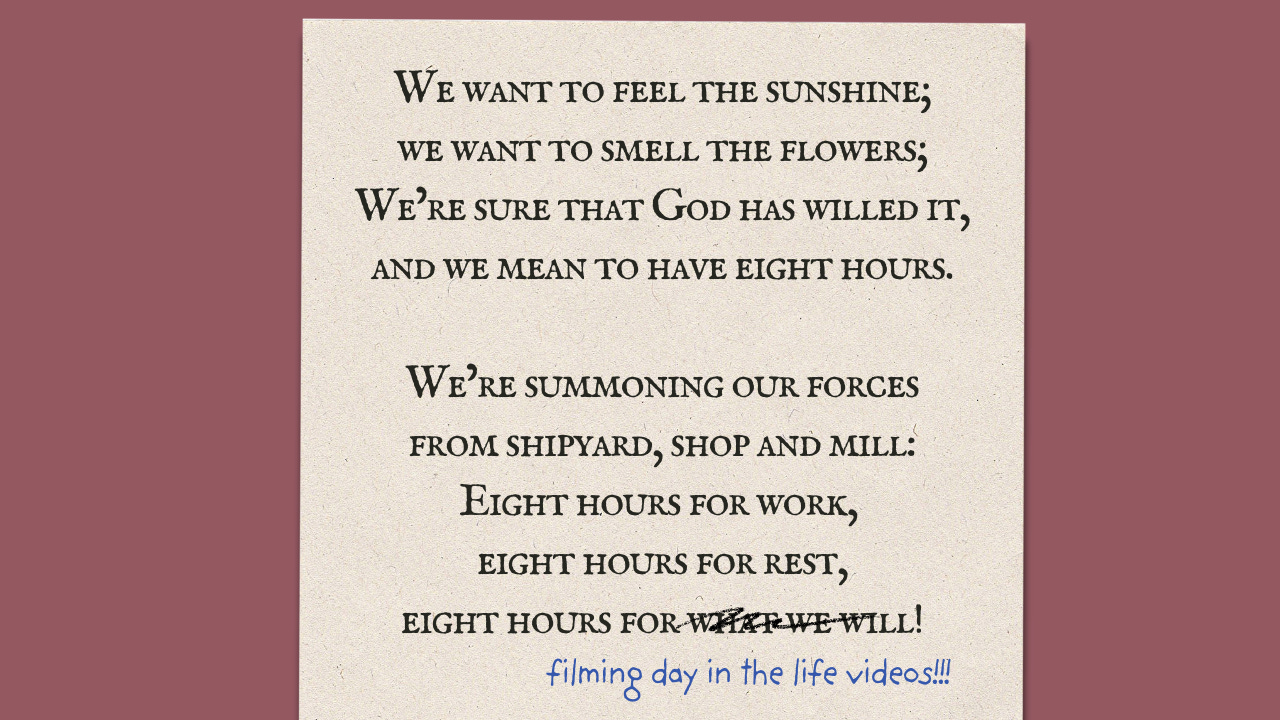

Then again, we also used to have more unions. Lest we forget on Labor Day that it was the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions that fought for 8 hours of work, specifically in order to make time for 8 hours of "what we will."

Many of our labor movements came crashing down in the 80’s, and with the erosion of collective bargaining power came a rise in gig work and 1099s. What full-time Uber Driver do you know that can realistically afford to strike? When the artist or the gig worker turns down the insultingly low-paying offer, there is an implicit assumption that someone—or some machine—will swoop in to take their place.

To me it would seem that we’re losing autonomy even as we appear to have more of it than ever before. Re-reading How To Do Nothing over the weekend reminded me of Fiverr’s “In Doers We Trust”2 campaign from 2016, which celebrated the “Doers” as those who replace lunch with coffee and never get enough sleep. Add in an increasingly algorithmic, enshittified, generative-AI-brainrot-slop-filled attention economy to a breakdown of unionization and a gutting of public arts funding, and is it any surprise that as artists we seem to have all become aspirational laborers—with most of us working for Meta or Substack or ByteDance or Google for free, and all of us fighting for a chance to be seen and therefore maybe one day also get paid?

In How To Do Nothing, Jenny Odell writes that "every waking moment has become the time in which we make our living."3

This is what I think about when I watch a day in my life vlog. All I can see is the camera, the tripod, the exchange of privacy for an expected potential reward. It’s what I think about when I see a 22 year old on Instagram asking for "feedback" on her "feed" or read a frantic Reddit post soliciting advice on how to "find a YouTube niche." It is easy, perhaps by design, to look at the young woman filming yet another Get Ready With Me video and assume that she is doing so from a place of vanity or ego. A more realistic view, in 2025, is that she's hoping to one day get paid.

She is responding to the culture around her, which promises her riches beyond imagination if she can only commodify herself into become a desirable and profit-generating "personal brand."

One day, the fairy tale goes, you will have so many followers and so much engagement on your posts that Bounty Paper Towels will pay you $25,000 for a 15-second video clip.

Never mind that Bounty used to have to pay for lighting and cameras and production and ad space for every piece of commercialized content they produce. Never mind that Bounty used to have to at least hypothetically lawyer their way out of paying worker's comp when the actress on set slipped and broke her leg.

By assuming all of the risk (otherwise known as ~becoming an entrepreneur~) our aspiring content creator stakes her claim on the entirety of the future potential reward. And as far as she knows, she also gets to do it on her own terms. She is working for herself, if you ignore the amount of time she spends polling her audience for ideas. She answers to no one, except maybe the algorithm. She even gets to make her own schedule—which of course means that when she wakes up at 4 am in a cold sweat and frantically checks her comment section to make sure no one’s yelling at her, that relationship to work is entirely her own choice, her personal responsibility. Such is the price you pay for “being your own boss.”

Economically, it also doesn't hurt that viewing her labor through an entrepreneurial, future-profit-oriented lens also makes it easier to justify spending money on beauty treatments and expensive camera lenses. These work/self improvements are, as Jia Tolentino writes in Trick Mirror, "a matter of both work and pleasure—of 'lifestyle.'" When your face and your body and your brain and your ideas are your primary means of paying the bills, it’s more a question of what isn’t a write-off than what is.

The aspiring full-time content creator or Substack writer or small creative business owner trying to expand beyond selling at the local craft fair knows that the more she can increase her share of attention and engagement and positive perception online, the more money she can maybe possibly someday make.

Why would she not at least try to improve her skin's texture or add some dimension to her hair? Why would she not replicate her most viral video, the one where her kids are snot-nosed and crying, the one that earned her family a spot on Good Morning America? Why would she not take that underpaid job with an over-demanding client to build up her portfolio?

We haven’t given her any other stories. This is the only myth she has.

Is It Cringe To Self-Promote Something Here?

Is there a way to get paid to do what we love without turning ourselves into algorithm-pleasing cyborgs who are constantly expected to sell our likeness to corporations for free?

That’s a big question, and one I think is best answered in a conversation with other artists who are also trying to carve out a way.

For me, I make what you might call a “Pretty Decent living” teaching marketing classes and selling digital products or services online. I make content that drives people to these classes or products or services, which is a significantly smaller feedback loop than I might find if my income were reliant on “going viral” all the time. All my business needs is one person at a time to see value in something I’ve created.

This is something I really love to teach other artists—how to design products and services people actually want to buy using the skills you already have, so that you can make some money while you practice and learn. The next course I’m teaching at the Pretty Decent Internet Café is called the Offer Design Sprint, and its main purpose is to help students create a product or service prototype—something you can make money from selling right away, while you learn more about who your audience is, what they need, and what you actually want to do.

For the first time ever, really, I’m opening up free tickets to the first class in the Sprint, which is all about Who It’s For. It’s next Tuesday, September 9, at 4 pm Eastern.

Together we’ll explore the relationship between what you want and what the audience wants, otherwise known as the relationship between art and content. We’ll also start on an Empathy Map together, and you’ll take home an experiment for interviewing people through a design thinking lens.

If you want to join us, you can RSVP here for free — just as a heads up, there are limited spots available, so if it’s showing as sold out please join the waitlist!

(Not) Getting Paid To Do What You Love by Brooke Erin Duffy (required reading imo)

The Gig Economy Celebrates Working Yourself to Death — Jia Tolentino for The New Yorker, 2017

This is why I rely on a full time job for my income and write my Substack for fun.

Brilliant article. I kept saying, "THIS IS ME! THIS IS ME!!!" I was dying for the answer to how to get past aspirational labor, but I guess the point is that its always a part of us as passionate creatives, we just have to learn how to maximize it?