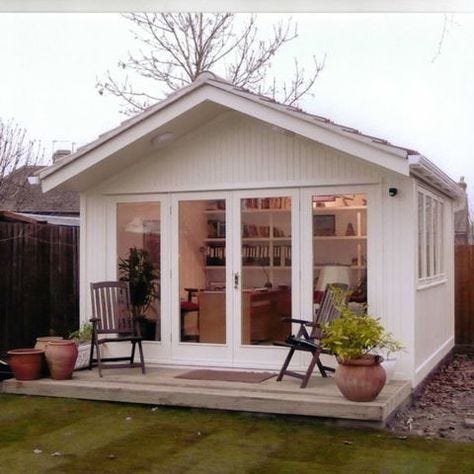

In my wildest dream, I work from a backyard garden studio. I wake up with the sun every morning, make coffee, then write while watching the birds.

In the grand scheme of human desires, my wildest dream probably seems quite idyllic and simple. I don’t really care to go to Mars or become a multi-millionaire. My definition of success does not hinge exclusively upon Forbes covers or bestseller lists.

Still, I recognize that underneath my reasonable and uncomplicated dream, there is also a powerful assumption.

The backyard garden studio library is not just a project I’d like to complete or an aspiration I’d like to achieve. It’s a symbol. In my dream, this imagined future self is not just in a beautiful place—she’s productive in a beautiful place. She’s consistently engaged with her work. She’s focused, accomplished, in “flow.”

My picturesque, writerly dream is a representation of my true desire: A desire for ease. When I say I want to sit in my backyard garden studio and write, what I’m really saying is that I want things to be easeful. In this imagination, I don’t struggle with laundry or credit card bills or completing items from my to-do list. The backyard garden library studio office of my dreams is, for me, a symbol representing what it means to be a woman with her shit together.

That is where the dream starts to feel “impossible.” Like many intuitive, creative people I know, I lived most of my life with undiagnosed ADHD. What this means that I’ve developed nearly three decades worth of thought patterns and systems that were, in practice, just an enthusiastic, easily distracted girl trying really hard all the time—and then blaming herself when things went wrong.

Last minute science fair projects. Obsessive time checking. Mnemonic devices. Flash cards. Email anxiety. Text anxiety. Social anxiety.

These were, for many years, the only tools I had for remembering—for “getting it done right” according to the rules and expectations surrounding me.

It’s not as if I wasn’t productive or smart or able to do important things before my diagnosis, it’s that the productive and smart and important things I was able to do all came at a significant cost. I passed the class, sure, but I never got enough sleep. I started a successful, fulfilling creative business, but I got myself into debt impulsively following every “best practice” along the way. I managed to clean the house before our guests arrived, but I was snappy and stressed the whole time.

It’s been three years since I was diagnosed with ADHD and just over a year since I’ve (finally) been able to access effective medication. Relatively speaking, I recognize that I am still learning to crawl.

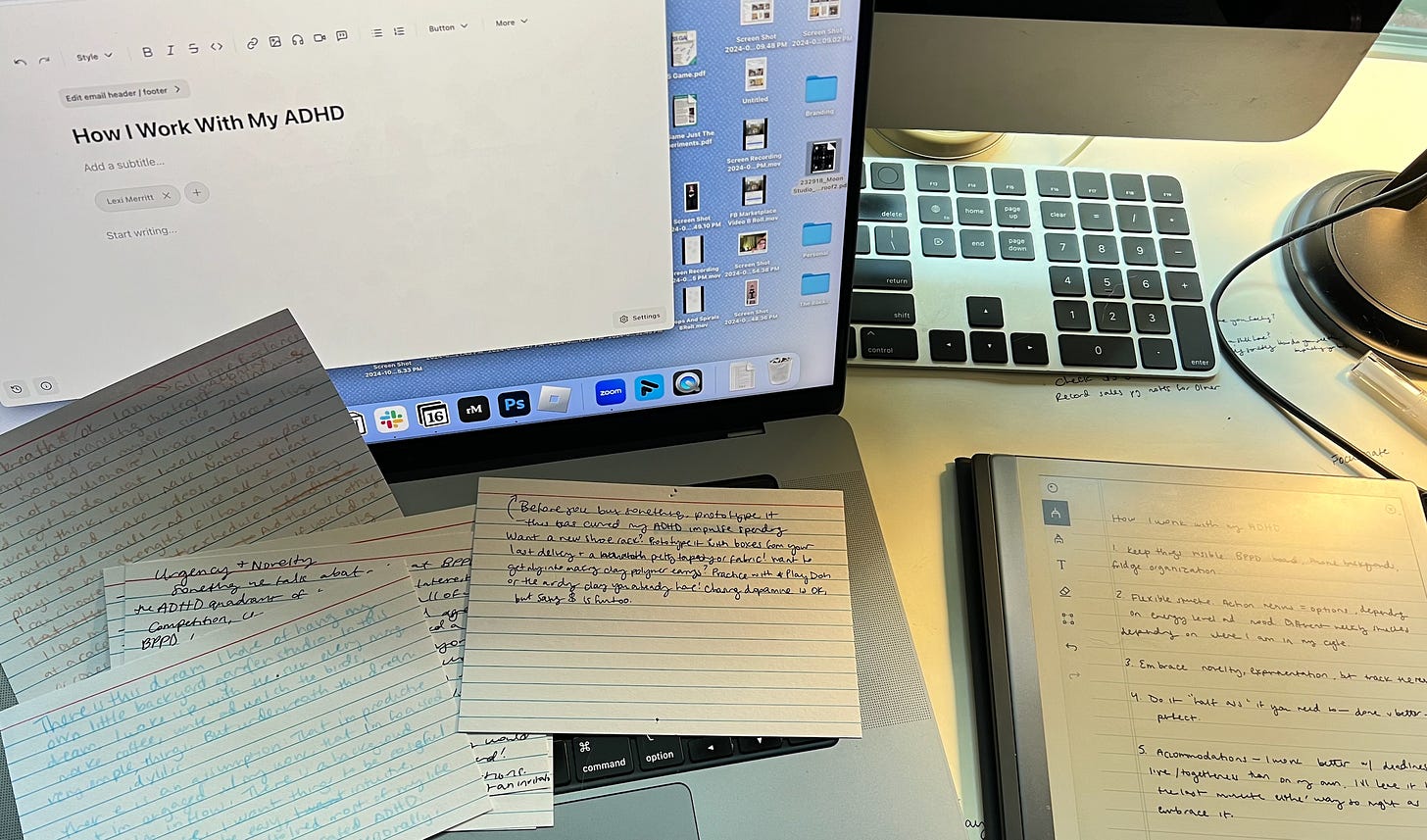

Fortunately, as those of us with ADHD intimately know, it doesn’t take long for a rabbit hole of obsessive research and experimentation to start producing meaningful insights. And so today what I’d like to share with you is how I’ve learned to work with my ADHD, particularly as a self-employed person who makes a living online.

How I Work With My ADHD: 5 Tips For Self-Employed Artists

1. Keep things (in)visible.

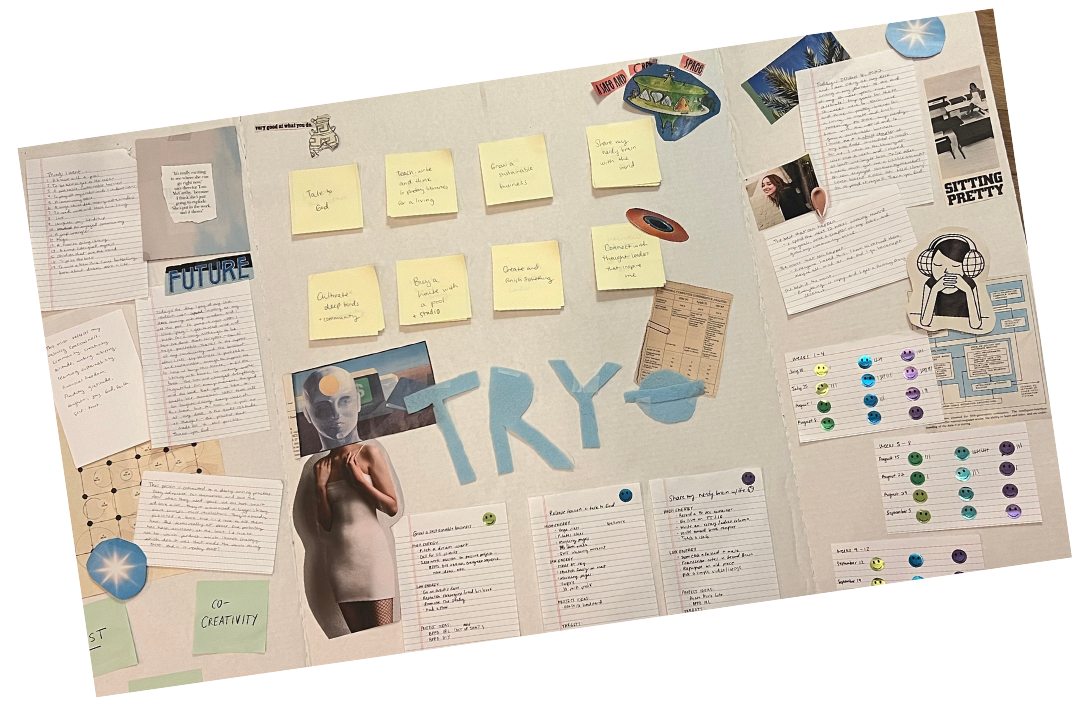

Those of you who follow my work online probably know how I feel about my Big Paper Planning Day boards. (We’re doing the retreat again next week and tickets are 50% off right now, if you want to join.) The reason they work for me is simple: There is a noticeable, measurable difference in my engagement with any given system when that system is visible to me.

I cannot, for example, rely on myself to play with my craft supplies instead of going on my phone when my phone is right next to my bed and my craft supplies are tucked away in a closet somewhere. For as much as I value simplicity and decluttering, some things just have to be in (and out of) sight.

Practically, what this means is that I keep anything I want to consistently engage with within arms reach. Per KC Davis’ advice, my fridge is reorganized often to ensure nourishing snacks are more visible than condiments and soda. My Notion workspace is structured to keep my to-do list and important projects top of mind. I keep a science fair board in my room/office with a list of abstract goals and action menus front and center.

And while I haven’t solved the problem of going on my phone first thing in the morning, I can at least recognize the variables that make it difficult not to. (Namely, that the phone is right there in front of my face when I wake up.)

2. Embrace novelty and flexible structure.

I know myself well enough to know that just about the time a routine starts working or a breakfast begins to feel reliable, I’m going to lose interest. For years, I considered this a character flaw. I called myself words like “flighty” and “inconsistent” and cracked on myself constantly for “not being able to stick to anything.”

In the years since diagnosis, I’ve learned to accept the idea that my nervous system responds quite well to novelty, and that this can be framed a strength just as easily as it can be bemoaned as a bug. Instead of expecting myself to stick to one thing forever, I ask myself to think (and plan) in cycles.

My morning routine on the weeks where I’m PMSing and bent over with cramps looks quite different than the one when I’m feeling fresh and full of energy. Every three months, I (re)draw a plan for my life. I feel okay starting a scrapbook knowing in a few months I might forget it exists, in part because I know the blank pages are as much an interesting and accurate representation of my life as the filled ones.

Of course, I still have responsibilities and there is still a “bare minimum” I strive to meet. I know, for example, that fresh air in the morning often generates optimism. I know that a slightly stoned walk at 5 pm is a laboratory for good ideas. I know that when I stretch I feel more at home in my body.

But I no longer expect myself to be “consistent” or “disciplined” at the sake of being well. I’m comfortable cycling through planners and rituals and tools, mainly because I know I can decide to speak kindly to myself either way.

3. Experiment with attention to results.

In order to sustain self-trust through the endless cycles of novelty and interest-seeking, I’ve learned how important it is to see an experiment all the way through.

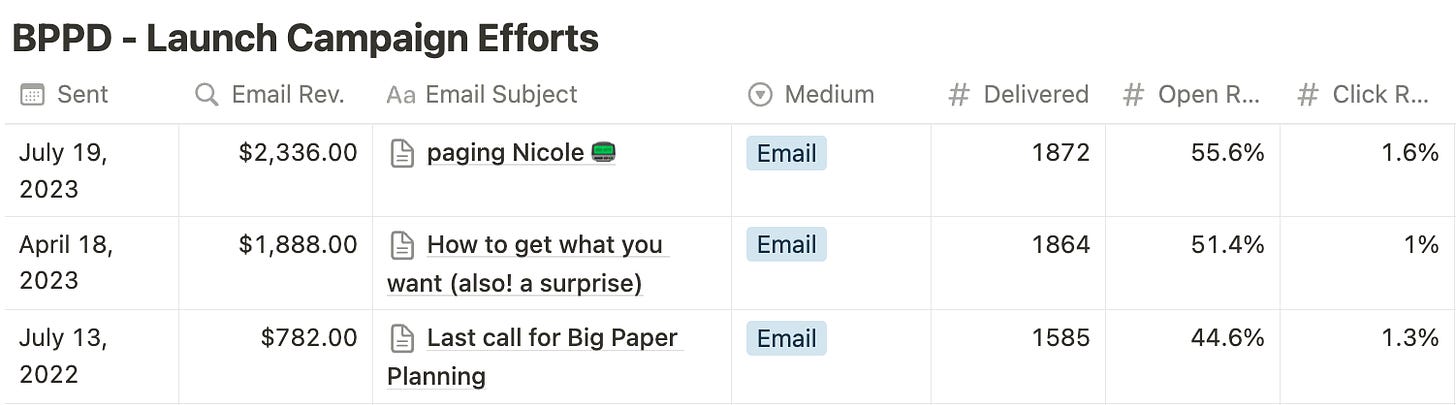

In my line of work (digital marketing strategy), there is a lot of messaging pointed at people who “throw spaghetti at the wall just to see what sticks.” What I’ve learned is, especially as a creative business owner with ADHD, I have to be free to throw that spaghetti at the wall. It’s an incredibly effective way to sustain motivation over time. The key thing is that I cannot stop there, at the throwing—I also have to pay attention to what happens next.

This is what we mean when we say life (and business) is an experiment. We enter into these experiments with questions and curiosities and hypotheses about what might work. The work begins when we wonder if the noodles are done and toss one at the wall to check. It continues to grow and develop as we log the results and come to conclusions based on what we observe.

What brand of spaghetti was it? How long did it boil? What was the temperature of the water, the size of the pot? This is the same line of questioning we might explore when we test out a new social media strategy or experiment with a new movement practice. So long as I can see and notice the difference that yoga has on my body, I can float in and out of a “consistent” practice as often as I need to. I trust myself to come back to those things that work and make me feel good.

4. Prototype. “Half assed” drafts are essential.

I’m a firm believer that ideas take shape when they are ready to be realized. We walk around with a notion in our head for years, then one day we stumble into just the right container and realize, “This is it.”

When that moment inevitably comes, I have to recognize that what I might see as “half assing it,” (a critique that haunted me through most of my formal education) is actually just the process of prototyping. And prototyping is essential—not just in design and entrepreneurship, but also in my day-to-day life.

I’m weary of the idea that I’ve “fixed” anything, mainly because I’m unwilling to think of my younger, less accommodated self as “broken.” But if there is one notable difference in my life since being diagnosed with ADHD‚ it is a measurable decrease in impulse spending. Medication has certainly helped, but I was able to make a change before I had access to it—and I credit that wholeheartedly to my obsessive interest in design thinking.

When I say prototyping, what I mean is drafting an uncomplicated (read: “half assed”) concept before spending weeks or months or hundreds of dollars making an idea real.

I’ll give you an example: A few weeks ago, I found myself deep in a rabbit hole of at-home espresso machine setups. Before my diagnosis, what this might’ve resulted in was an impulse purchase of the whole kit and kaboodle of tools. (This is, unsurprisingly, exactly how I got myself into credit card debt in my early 20’s.)

Now that I think in prototypes, my instincts and impulses have changed. Sure, I might still make a Notion doc listing out all of the tips and recommendations I’m seeing online—but I also look first to what I already have.

How might I improve my iced coffee ritual without spending a single dollar? Can I clean and rearrange the bar cart where my perfectly good Nespresso currently sits? Do I need to buy a fancy tea bag organizer, or can I use cardboard from around the house to restructure the old cigar box we’re already using?

This same principle of prototyping is generously applied to any beautiful idea that pops into my brain. I taught my course Internet Business live for two years before I asked my best friend to spend a weekend recording a “professional” version in my living room. I curated a Pinterest board of outfit ideas for months while I saved up to spend a day at the thrift store reinventing my wardrobe. While I wait for my backyard garden library “she shed” studio dream to be realized, I frequently rearrange the small corner of my bedroom where I currently work.

These small prototypes help me test out the most basic version of an idea, fine-tuning it in response to feedback before I make a significant investment of time, money, or energy. For my life, my business, and my wallet…this has made all the difference.

5. Do it together, do it live.

My final lesson is, like the others, as much about self-compassionate life design as it is about running a business with ADHD.

Long before we had the language to describe what was happening inside our brains, my best friend and I recognized that cleaning was easier with the other person in the room. This, of course, is what we now call “body doubling.” What I didn’t know then was how transformative this simple practice could be.

I can tell you now, looking back, that I’ve designed every aspect of my business around body doubling, and it is as beneficial to me as it is to my clients and customers. When I jokingly called Pretty Decent an “Internet Café” in 2018, I had no idea how helpful that framing would be in the years to come.

Here’s what I know about myself: I know that I will be editing my slides for a presentation up until the moment I go live. I know that I bought dozens of marketing courses over the years and never finished them. I know that no matter how far the deadline for a project deliverable extends out, I will most likely have the “Aha!” moment in the 24 hours before it is due. I know that in each of these experiences, I am nowhere near alone.

Again, this all boils down to self-compassion and trust. Instead of seeing the person I’ve been all my life as a collection of bugs in need of fixing, what if I saw myself through the lens of strengths and possibilities? What if I designed marketing courses explicitly for people who also need someone to sit in the room with them while they do their laundry? What if I structured my services as a retainer, as if my clients were hiring me to come work inside of their business one day a week?

In other words, what if what works for me works for others, too?

These are the frames and questions that have transformed my business and life. I could talk your ear off about the measurable, noticeable results: More money, less debt, more fulfillment, better moods, stronger relationships, easier days.

But if you’re still reading by this point, it’s probably because you, like me, are always seeking solutions. And to that I would say: Please, please experiment. Try something once without the expectation that you’ll stick to it 31 days from now. Pay attention to what follows—both how the world responds and how you feel inside.

Most importantly, be good to yourself. It is not your “fault” when a system or structure or SMART goal action plan was not designed to accommodate your needs.

Your creativity is a gift.

Your million and one ideas are evidence of abundance.

Your rabbit holes of varying interests are the threads that make brilliant, interdisciplinary insight possible.

Follow them. And trust at every step and pivot and decision along the way, you are allowed to give yourself a big gold star for trying.

One more thing: If you want to explore what’s underneath your dream, here’s a Notion journal of writing exercises I ask participants to complete before Big Paper Planning Day. Even if you can’t make the retreat, I have a feeling you’ll find something interesting there.

Love this piece. Such great insight into ADHD (which my hubby has). As I read this, it also felt like a well thought out argument for compassion, experimentation, and lightly structured out of the box thinking. And I TOTALLY share your vision for a garden office! I sit outside to work whenever I can. See you at Big Paper Planning Day!