“I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what I fear. Why did the oil refineries around Carquinez Strait seem sinister to me in the summer of 1956? Why have the night lights in the Bevatron burned in my mind for twenty years? What is going on in these pictures in my mind?”

— Joan Didion, “Why I Write” (1976)

I’ve always been impressed by people who can write the thesis statement first. For as long as I can remember, I’ve never known what I’m trying to say until I write it down. This, among many reasons, is why I’d never make it on reality TV.

On Survivor, pen and paper is considered a “luxury item.” The game, which is to say the spectacle, relies on contestants doubting their own minds. Strategy and intentionality doesn’t make for very good television—at least, not when everyone has access to it. It’s fun to have one or two charismatic Boston Rob mastermind types, but the confessionals stop being fun when the whole cast is clear-headed. As an audience, we delight in the dramatic irony of someone missing the mark. We like to watch the point, the truth, whoosh right over their heads.

A few years ago, while at a murder mystery dinner party, I was shocked to realize that I’d written down the correct name of the “murderer” at the beginning. As the party went on and I got progressively more tipsy, I forgot all about my pen and paper (which I was mostly using as a bit) and voted wrong, with total confidence, in the end.

I trusted what I thought more than what I’d written down, which is to say I didn’t really think very much at all.

I say all of this to echo what writers have been saying for a very long time: That writing is thinking, and thinking is writing, and that there’s no good reason to delay writing until you figure out exactly what you’re trying to say.

Every time I sit down to write, I’m confronted with the fact that I have absolutely no idea what I’m talking about (yet). When I don’t want to acknowledge that something is wrong, I avoid writing like the plague, despite the overwhelming onslaught of evidence that tells me writing absolutely will help.

In moments of crisis and depression and self-doubt, I’ll do anything to avoid acknowledging the truth of what I know. I’ll clean the baseboards and build a three story house in The Sims. I’ll invent a million and one reasons not to write, taking special care not to write any of these reasons down (because, of course, writing them down would make their absurdity apparent).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this confrontation between what we know and what we don’t is an essential part of learning. In one study, participants that engaged in drafting essay-like summaries before a test performed better than those that took notes and memorized key terms.

Writing asks us to recall, to reorganize, to structure information, to find the links between various competing narratives. Writing offers us critical distance from our thoughts, which helps us spot emergent patterns and connections.

It’s easy to imagine how helpful this might be on an island where everyone is lying to each other, or at a dinner party where almost no one knows the truth. But as artists, as thinkers, as people who are counting on our observations and knowledge to get us from where we are to where we want to be, I can’t help but think of our pens and diaries as “luxury items,” too.

Which is why I want to offer you a tool.

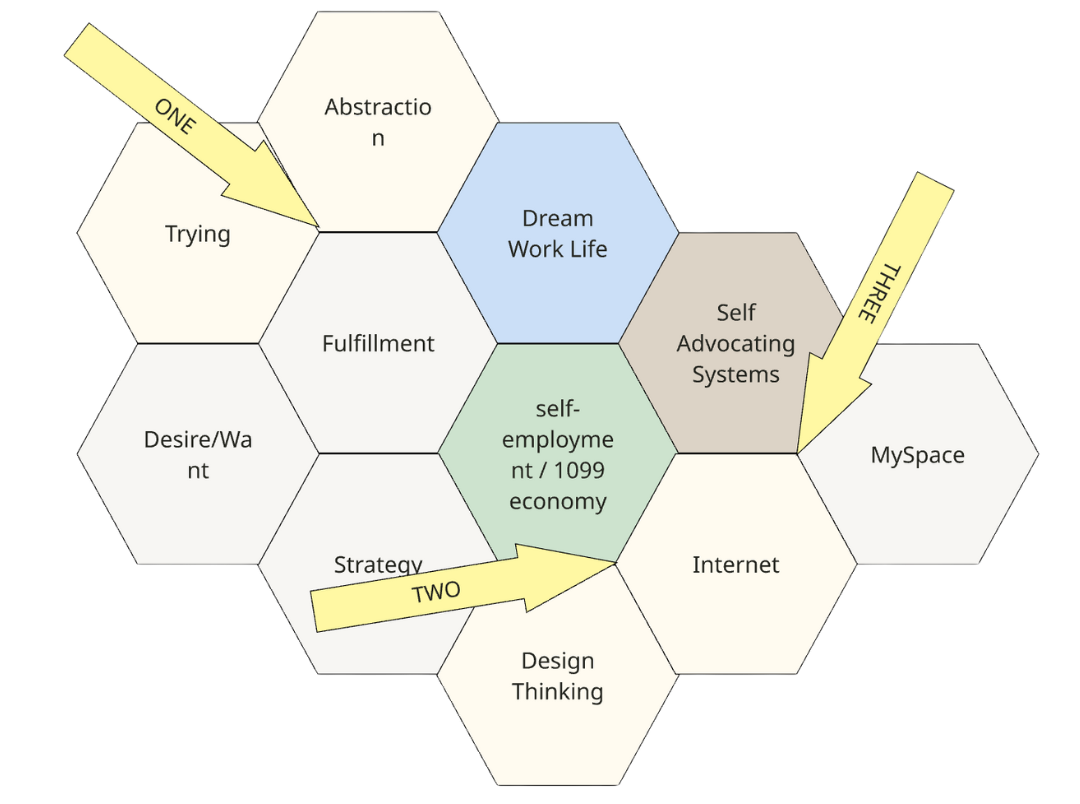

About a month ago, I stumbled into a teaching exercise called hexagonal thinking, which prompts students to find the connection points between various terms and ideas. (Nerd alert: Yes, this is what I do on Pinterest in my spare time.)

Earlier this week at a Copywriting Lab in The Study, I tried it on a whim, thinking it would just be a warm-up. We spent the whole time on it. The feedback blew me away.

There is something very surreal and Dream-Work-Life-y to me about the fact that a large part of my job is watching very smart people, in real time, figure out what they’re trying to say. At the end of the lab, when we came back together to externally process what we’d each come up with, I was delighted to find myself shouting “YOU MAKE SENSE!” over and over again.

The exercise, which I’ve adapted into a 25-minute thinking tool called Method Your Magic (free!), is simple:

Brain dump your personal vocabulary.

Write each term/subject/interest onto a hexagon for arrangement. If two or more hexagons are related, you can illustrate that by making them touch.

As these connections and patterns emerge, highlight a few that stand out to you with numbered arrows, then use these numbered cues to “explain your thinking,” aka WRITE.

If you don’t feel like cutting out a bunch of hexagons, I made a Miro board template you can use to try it out today.

What I think might happen, if you’re a Professional Smart Person, is that through this exercise you’ll start to see a framework emerging—something you can use to illustrate your specific, interdisciplinary expertise.

What I know will happen, regardless of who you are or what you do, is that through this act of writing you will begin to see that you do, in fact, make a whole lot of sense.

I’ve heard it said that the first draft is a writer telling the story to herself. This is as true for novelists as it is for diarists and margin-scribblers. In writing, we find the answers to the questions we can’t escape. As we shift words around, looking for the truth at the heart of the matter, we get somewhere new.

This requires at least some degree of confidence—maybe even arrogance, if we accept Didion’s assertion that “writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind.”

Perhaps this is why I believe everyone deserves a private place to write, a blank space where the only reader is Me, Myself and God. Perhaps this is why I’m so invested in building free-writing prompts into every marketing and business class I teach.

Writing is how we decide what to pay attention to. In writing we solve problems, if only because, by writing for long enough, we actually begin to acknowledge them. Writing is a survival strategy in a world determined to produce and manufacture doubt about what we see, hear, and believe.

Writing is thinking without the burden of clarity. In writing we take up space, filling blank pages with evidence of who we really are and what we really believe.

Writing is remembering. Writing is self-advocacy. Writing is the answer, no matter the question. Writing is how we go on.

Thanks for reminding that writing is not the end goal but the way through 🙌

Exactly the gentle reminder and motivation I needed to revisit the page. Lately, I’ve been struggling with ideas that I feel I can connect in my mind and not on paper!! So looking forward to trying this hexagon model 👏👏 thank you 🥹🥹